MCA Newsletter

November 2008

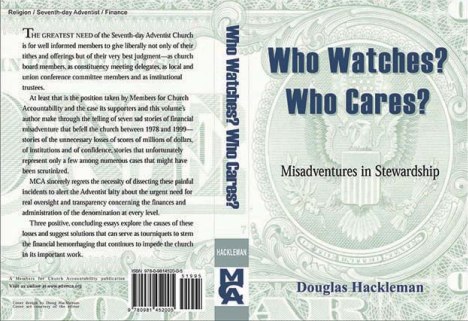

As reported in our last newsletter MCA published a book in May 2008 entitled Who Watches? Who Cares? documenting the unnecessary losses of scores of millions of dollars between 1978 and 1999. There is no indication decades later that there is anyone who watches or anyone who cares. Excerpts from that book were included in our last newsletter. MCA thanks you if you have already purchased a book. Because we are anxious for the book to be distributed extensively among lay church members, we are requesting that members of MCA purchase a book for a friend or send MCA the name and address of a friend, or friends, that you believe should have the book.

Seven Stories! Documented! Compelling!

To order: Send $25.00 to

MCA

9450 Jeffery Drive

Redlands, CA 92373

A six page condensation of the first chapter with questions to ponder follows:

A Tale of Two Institutions

Fuller Memorial Hospital's misadventure began in 1977, when its administrator, Gerald Shampo, involved the 82-bed, Seventh-day Adventist psychiatric hospital in a limited partnership of his own devising that was created to finance, build and manage a 160-bed nursing home facility in nearby Pawtucket, Rhode Island. The nursing home was funded by the Fuller Memorial Hospital, built by the limited partnership headed by the hospital's administrator and then sold to the very hospital that underwrote its construction.

In February 1982 during a constituency session Cliff Turner, an elder of the Foxboro Seventh-day Adventist Church, overheard someone say that the Adventist Church did not own the Pawtucket Nursing Villa. This was at variance with what Atlantic Union president Earl W. Amundson wrote in the Atlantic Union Gleaner since he included Pawtucket Nursing Villa as one of the nine health-care institutions owned by the Atlantic Union.

At the time of MCA's symposium in October 2001 we had copies of three important documents referenced in the story that follows.

Turner visited the Rhode Island State House and the Pawtucket City Hall. As he examined an amended limited partnership agreement Turner discovered that at the inception of the Pawtucket project Fuller Memorial Hospital, as a limited partner, had owned only 24 percent of the Nursing Villa.

The controlling general partner, in this limited partnership, was composed of three individuals, Gerald Shampo, the Fuller Memorial Hospital administrator, and two Rhode Island developers, Eugene Sirois and Anthony Lawrence. Fuller Memorial Hospital, as limited partner, had invested $145,000 to acquire the building site property. In contrast, the general partners, Shampo, Sirois, and Lawrence, owned 76% interest in the Pawtucket Nursing Villa for an investment of $1.00 each!

On April 7, 1977, the three general partners executed the limited partnership, along with Stuart R. Jayne, vice president of the Fuller Memorial Hospital board of trustees and Southern New England Conference president, whose signature committed the Hospital to a financial disaster.

Construction of the Pawtucket Nursing Villa was financed through a Housing and Urban Development (HUD) mortgage of $3,163,000.00 acquired by Fuller Memorial Hospital, and the Villa opened for business on April 23, 1978. The general partners, who owned 76 percent of the facility, legally owned 76 percent of the $3.2 million construction mortgage, while Fuller Memorial Hospital was legally liable for 24 percent of the loan. However, the general partners made no mortgage payments.

Five weeks after the Pawtucket Nursing Villa opened for business, May 30, 1978, the Fuller Memorial Hospital Executive Committee voted to purchase the 76% interest in the Pawtucket Nursing Villa from the general partners Shampo, Sirois, and Lawrence for $560,000. The sales "Agreement" was finalized on December 29, 1978.

The "Agreement" committed Fuller Memorial Hospital to paying $560,000 principal and $88,886 interest to the three general partners. The Fuller Memorial Hospital board of Trustees obligated Fuller Hospital to the following payment schedule:

| Date | Payment | |

| December 31, 1978 | $90,000 | |

| December 31, 1979 | $81,800 (plus 6% interest $28,200) | |

| December 31, 1980 | $86,708 (plus 6% interest $23,292) | |

| December 31, 1981 | $91,910 (plus 6% interest $18,090) | |

| December 31, 1982 | $97,425 (plus 6% interest $12,575) | |

| December 31, 1983 | $112,157 (plus 6% interest $6,729) | |

| Total: | $560,000 (plus interest $88,886) |

According to the Agreement,

"Notwithstanding anything herein contained to the contrary, the percentage interest with respect to profits and losses of the said Limited Partnership shall be divided among the General Partners and the Limited Partners as follows:"

| Year Ended | General Partners | Limited Partner |

| Dec. 31, 1979 | 70% | 30% |

| Dec. 31, 1980 | 64% | 36% |

| Dec. 31, 1981 | 58% | 42% |

| Dec. 31, 1982 | 52% | 48% |

| Dec. 31, 1983 | 46% | 54% |

| Dec. 31, 1984 | -0- | 100% |

From the payment schedule and division of profits and loses it is clear that although Fuller was to pay nearly 20 percent annually on the principal, the hospital only acquired an additional 6 percent of ownership each year. No doubt the general partners expected there would be profits during the five years of operation and thus the agreement was structured so that they would receive the preponderance of any profit during the first four years of operation. The agreement also contained a clause concerning prepayment by the limited partner.

"SDA [Fuller Memorial Hospital] shall not have the right to pre-pay any or all installments of either principal or interest, without first obtaining written consent of the General Partners, and in all events, and under no circumstances, shall any prepayment be made during the period of the first year, so that the General Partners may take advantage of the Installment Sales provisions of the Internal Revenue Code of 1954."

Through the initial partnership agreement and the sales agreement Fuller Memorial Hospital paid a great deal of money for massive liabilities. The three General Partners, Shampo, Sirois, Lawrence, and J. L. Dittberner, chairman of the Fuller Memorial Hospital board of trustees and outgoing president of the Atlantic Union Conference executed the Sales Agreement on December 29, 1978.

A six page Memorandum from Steven White, director of internal auditing of AHSNorth, dated November 23, 1981, confirmed the above payment schedule and percent ownership of the limited partnership. The report also noted Pawtucket's annual operating loses.

| Year | Annual Loss | |

| 1977 | ? | |

| 1978 | $ 340,019 | |

| 1979 | 154,394 | |

| 1980 | 47,266 | |

| 1981 (first nine months) | 46,970 |

This excluded any transfers related to the December 29, 1978 agreement.

The audit confirmed that Shampo, Sirois, and Lawrence made no personal investment in Pawtucket.

Finally, the auditor enumerated thirteen issues that required resolution. The following are the most intriguing:

6. We were informed that the partnership tax information forms still allocate the losses of Pawtucket to the partners. From the accounting records, we noticed that the losses distributed to the three individual partners were even more than what the December 29, 1978, agreement called for. If the partners are not liable for these losses, then is Pawtucket subject to possible tax litigation for distributing the losses to the partners?

10. Eugene Sirois, one of the original partners, is drawing a salary of $17,500. His title is comptroller but he has no duties at Pawtucket and we were informed that he is rarely there. Pawtucket has a controller who is responsible for the financial operations. We were informed that Mr. Sirois has "connections' at the county property tax office and this is why he was retained.

12. Since Fuller owns and controls Pawtucket, can Pawtucket be set up as a 501(c)(3) corporation and avoid the $57,000 annual property taxes? If so, why was this not accomplished at the time of the sale?

Cliff Turner, a Foxboro Adventist church elder, met on March 16, 1982 with Stanley Steiner, president of the Southern New England Conference. Although Steiner's Conference presidency began in June of 1981, three years after the Pawtucket sale, he was secretary-treasurer of the Fuller Memorial Hospital Board of Directors and therefore an appropriate person for Turner to query. Elder Steiner appeared to be concerned by information the layman presented to him, but he stated, according to Turner, that he had "no knowledge of the situation." Eleven days later Steiner visited the Foxboro SDA Church where he responded to questions about the Pawtucket matter by saying he still had no information.

Turner and others were bewildered by the discovery that the president of Southern New England Conference and vice chairman of the Fuller Memorial Hospital board of Directors, was unaware of the hospital's partnership agreement and purchase agreement involving the Pawtucket Nursing Villa. Cliff Turner arranged to meet on April 15, 1982, with Elder Earl W. Amundson who had replaced J. L. Dittberner as president of the Atlantic Union Conference three years earlier.

By virtue of his position Amundson was a trustee on the Fuller Memorial Hospital board of Trustees and shared the chairman and vice-chairman positions on the board of AHS/North with Robert Carter, President of the Lake Union Conference. The Turner meeting with Amundson lasted about an hour and a half.

James Ware, an elder of the Brockton SDA Church joined Turner in the struggle to get an explanation from their church officials concerning justification for administrative fiduciary failure. They were joined by two lay church members, Sulo Aijala and Tim Schnell.

Over the next twenty months these lay church members experienced first hand the delaying tactics that church officials use when they are caught with their "hands in the cookie jar." A classic stall occurred when Steiner called Turner on October 5 to say that the Pawtucket matter was placed at the end of the board's agenda and was not discussed!

On December 15, 1983 another note from Steiner apologized on behalf of Amundson who, Steiner said, "asked me to send you a copy of the letter which I sent to all Southern New England Conference pastors this week." The Conference president's December 8, 1983, letter to "Dear Pastors" was considered by the Atlantic Union President and the New England Conference President to concluded their investigation and bring an end to inquiry from lay persons. The entire letter is reproduced in this chapter, but one sentence will reveal the flavor of this communication: "To state this concept clearly Gerald Shampo will not receive any material or financial gain whatsoever from his having been a partner in the construction and subsequent sale of PIH to Fuller." To their dismay, the book on the Fuller-Pawtucket case was far from closed.

At this point Doug's tenacious investigative effort uncovered John Normile, an individual previously unknown to MCA.

In the very month that Steiner sent out his letter to all his conference pastors, December 1983, certified public accountant John Normile joined Fuller Memorial Hospital as its new director of fiscal support services. Within a year of his arrival Normile resigned his position, when he "came to the conclusion that the current Chairman of the Fuller Board, Gerald Shampo, is involved in a continuing pattern of fraud and abuse against Fuller." Normile wrote Fuller Memorial president Ronald Brown, "It now appears to me that . . . there is a concerted effort to cover up what can only be described as the misuse, by Shampo, of a position of trust for private gain."

In a letter to the Fuller board, Normile challenged the veracity of Steiner's letter to the Southern New England pastors:

Here [in Steiner to "Dear Pastors"], less than two months after the October 18, 1983 [Fuller Memorial board] meeting where it was only "suggested" that Shampo never planned to keep any of the money, Elder Steiner tells the pastors that Shampo "had in fact always planned to follow the original agreement which he made with the Fuller Board in the beginning. In fact Steiner's letter cited no documentation of any "original agreement" that Shampo "had made with the Fuller Board in the beginning . . . . that he would not retain any of the gains," because there was no such agreement. Even if there was such an understanding, it would have only accounted for about one-third of the money lost to the general partners--the more than a quarter of a million dollars that went into Gerald Shampo's pocket.

Following his resignation December of 1984, Normile wrote the Fuller Memorial Hospital president an eight page letter documenting with attachments what he believed to be the evidence in the Fuller-Pawtucket relationship for fraud, self dealing and tax law violations. Eight months later Normile sent a seven page letter making the case to the Fuller Board of Trustees.

Not only did the illegitimate assumption of losses damage Fuller financially, it exposed the hospital to legal jeopardy and enormous additional expenses. Normile's letter to the Fuller Trustees was direct:

"The Board of Directors of Fuller Hospital, in violation of tax law, permitted substantial Nursing Home losses to be allocated to Shampo and his associates for the next several years after Fuller owned 100% of the Nursing Home. This, of course, directly benefited Shampo since he could offset these losses against his other income. These losses should not have been allocated to Shampo after the December 29, 1978 sales agreement since at this point the Limited Partnership was dissolved, having sold its only asset, the Nursing Home, to Fuller. This cost Fuller several hundred thousand dollars in real estate taxes which it should not have paid as a tax exempt organization. Payment was made however to protect the sham that the Limited Partnership still existed so that the Nursing Home losses could be passed through to Shampo."

Using White's "Memorandum" figure of $57,000 annual property tax, by the time Normile wrote the board in late 1985, Fuller unnecessarily lost an additional $399,000.

Not only did the general partners neglect to pay their legal share of the Pawtucket loses, but Fuller facilitated Shampo, Serois, and Lawrence to claim the Pawtucket loses as their own. As a result the three general partners realized an enormous illegal tax benefit and simultaneously, placed Fuller's non-profit status at risk. Normile's letter to the board informed them of a fact they should have already known:

Fuller is a tax exempt organization and has no tax problems. Is the Board here admitting that again they are using a tax exempt organization, in violation of their charter, to structure a deal so a corporate officer can have personal gain?

For the Fuller Board the most generous characterization that Normile could muster was "negligent." Normile believed that the available documentation demonstrated "that the Fuller and Adventist Health System North Boards of Directors were negligent in not taking legal action against Shampo and his associates."

The board's failure to remove Shampo from his hospital administrative position once they understood how he benefited from his conflict of interest in the Pawtucket Nursing Villa, Normile considered "either joint stupidity or collective collusion."

Normile informed the members of the Fuller board in writing that their "failure to exercise their fiduciary responsibility resulted in the fraudulent depletion of Fuller's assets of at least $720,000," a depletion that was the direct result of Shampo's severe conflict of interest, which enabled him to self-deal while he was the administrator of Fuller Hospital and a general partner in the nursing home. Normile went on to "question the judgment of the Fuller Board members who permitted this transaction, and then, "to add insult to injury elevated him to Chairman of the Fuller Memorial Board of Directors."

In his resignation letter to Ron Brown, Normile expressed disbelief at the "length time it has taken not to resolve the matter. It has been thirty-four months from the first hint to the present." He was deeply disturbed by the concerted effort to cover up the misuse of a position for private gain.

Normile's deepest "sense of outrage" was reserved for the "the continued attempts to frustrate the efforts and, at the same time, insult the intelligence of those people trying to get to the truth and set things right." He concluded:

"Ron, had I known the depth of this nursing home scandal, I never would have accepted a position with AHS/N and come to work for Fuller. It's not something that's in the past as you said. The scandal continues since no action has been taken against those involved and who continue to be in leadership positions."

In the summer of 1984 Amundson resigned in protest from his position as a director of the Fuller board, and late in the year Amundson and Steiner jointly filed a minority report on the Pawtucket matter with the General Conference.

Note: Despite the audit report from Steven White and multiple letters with documentation from John Normile to the Fuller Board, the AHSN Board, and the administrative leadership, Gerald Shampo was not fired by the same leadership that filed a minority report to the General Conference. In July 1985 the Southern New England Conference Executive Committee resolved "to request that the employment of Gerald Shampo by Adventist Health System North by terminated by September 1, 1985."

Questions to ponder:

Presumably the Fuller Board of Trustees previously discussed the feasibility of constructing a nursing home in Pawtucket sometime prior to April 7, 1977.

Now imagine yourself as the chairperson of the Fuller Hospital Board and the hospital administrator requests a meeting with you. He proposes a limited partnership to finance, build, and manage the proposed Pawtucket Nursing Villa. He has a partnership agreement in hand that indicates himself as the general partner with 76% interest and no financial contribution and your Fuller Hospital as the limited partner with 24% interest and a contribution of $145,000. As chairperson of the Fuller Board you are now asked to sign and date the partnership agreement.

1. What would your response be to such a proposal? If, in this simulation, you signed the partnership agreement please skip the following questions.

2. How do you explain Stuart R. Jayne's willingness to sign the partnership agreement?

3. How do you react to the fact that the Fuller Hospital administrator was also a member of the Fuller Hospital Board of Trustees?

4. Presumably the board of Adventist Health System North (AHSNorth) appointed Shampo to the chairmanship of the Fuller Hospital Board of Trustees with the consent of the Fuller Board. Undoubtedly AHSN was aware of the limited partnership agreement and the sales agreement, if by no other means than the AHSN audit report by Steven White. How do you explain the action of AHSN to promote Shampo to the chairmanship of the Fuller Board?

5. How do you explain the failure of the Fuller Board of trustees to terminate Shampo as Fuller Hospital Administrator?

To Order: Send $25.00 to

MCA

9450 Jeffery Drive

Redlands, CA 92373